BY KATIE THOMAS

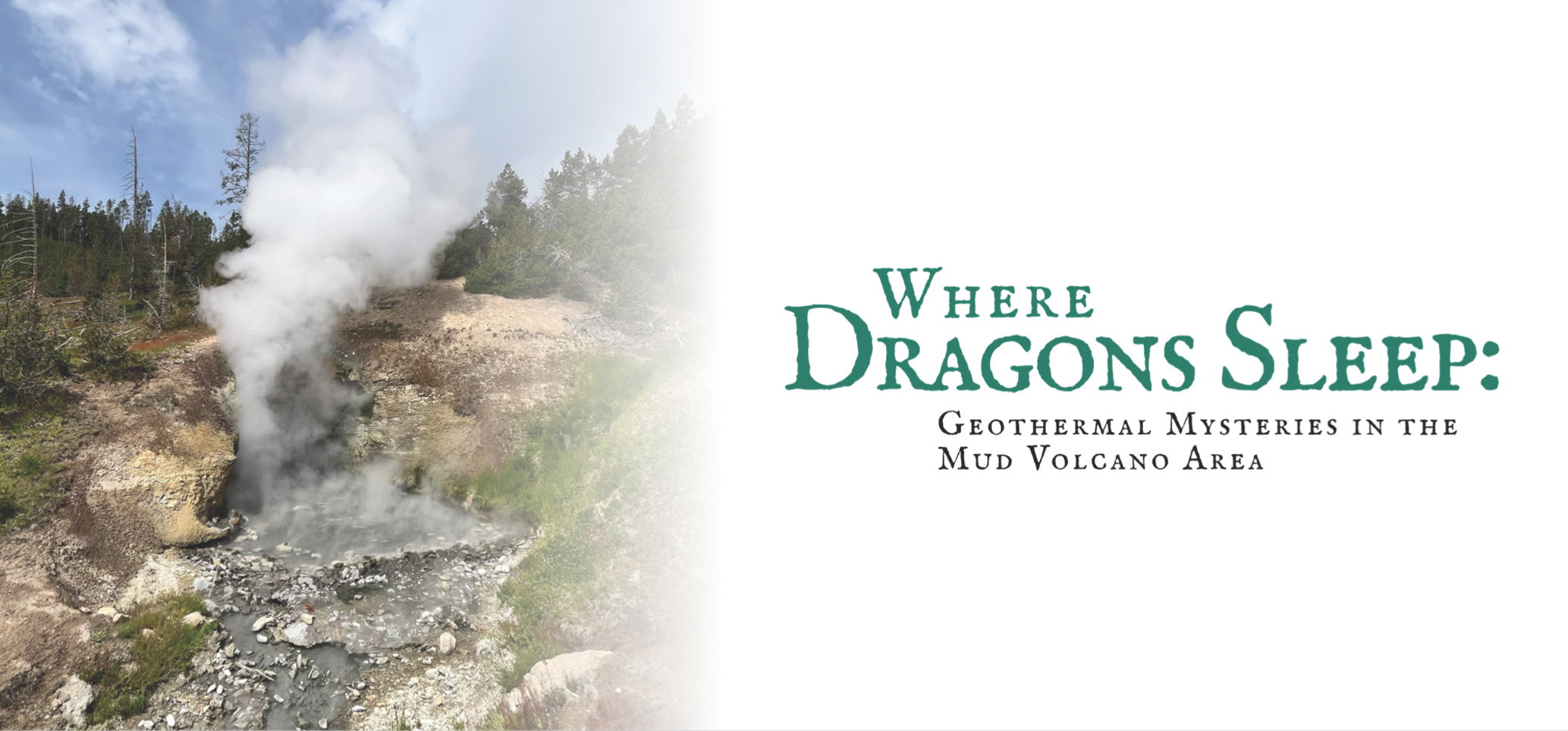

Near the 45th parallel north on the Gardner River in Yellowstone National Park, a steaming waterfall once rolled over travertine rocks into the stream. Rings of river stones formed pools where the 140-degree water mixed with the icy temperatures of the Gardner, creating the Boiling River: a natural hot springs two miles south of the park’s North Entrance, where locals and visitors alike converged year-round to immerse themselves in the thermal pools.

First documented by the Hayden Geological Survey in 1871, the thermal features around Mammoth are literally untouchable, with this one exception. Because the spring flowed into a running river, it was possible and legal to bathe in this hydrothermal phenomenon.

It was early October, and the cottonwoods were turning brilliant gold. Breathing in the sharp smell of sagebrush, we trudged the half-mile trail upstream to the pools. Bathers were hanging their towels and clothes on the buck-and-rail fence, which I came to understand was the only option – no changing rooms here. We lowered ourselves into the steaming water, groping the algae-covered stones to navigate the current. Eventually we found spots in a little cave of overhanging rocks and commenced marinating ourselves in the swirling 100-degree temperatures.

Dangers notwithstanding, I was a Boiling River zealot from that point on. I begged my parents to take us there for special occasions – my birthday, New Year’s Day, Tuesday. Summoning the smell of sulfur and the image of limestone deposits, I’d get ants in my pants to go back to that water.

Once, Mom made the mistake of going on a ladies’ trip without the rest of us (I forgave her eventually), and she described Yellowstone facials: smoothing river mud all over one’s face and baking it in the sun.

Once I turned 18, I was free to move to Mammoth to be closer to my favorite spot, and that’s exactly what I did. The summer after my freshman year of college, I worked as a housekeeper and spent my free time soaking and swimming in the Gardner. It was scorching hot during the day, so the river was a welcome respite from the sun. But at night, I would sneak without compunction down to the springs with my friends for a nighttime soak.

In time, I found that I preferred the Boiling River during winter. It was less crowded, for one thing. But frosty hot springing was not for sissies; it meant you had a chilly hike and uncomfortable outdoor changing experience ahead. In fact, climbing out of the steaming pools in a blizzard without whining was a statement of your ruggedness. I became skilled at speed-dressing, and once wore Tevas in February just to show off.

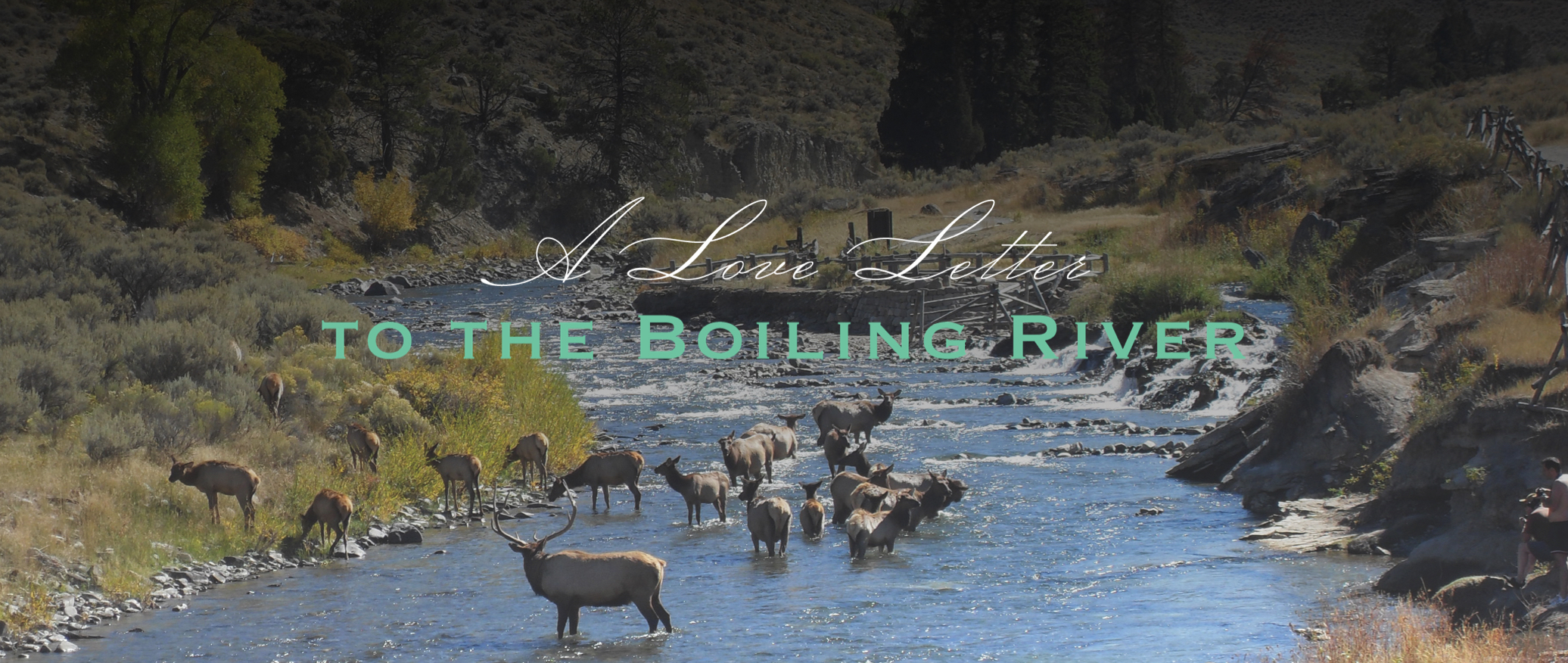

Sitting in that surging, cozy-hot river amongst pillows of steam and blankets of snow couldn’t be more heavenly. I’m grateful for all the times I relaxed in that water while herds of elk or bison sauntered past me through the river, all of us undisturbed by other humans. I felt sorry for people who had to settle for chemical-filled hot tubs in loud, crowded places. I needn’t have worried, because this experience had an expiration date – in my lifetime, anyway.

On June 13, 2022, a 500-year flood hit the northern section of Yellowstone Park. The area got about eight inches of combined snowmelt and rain within a 24-hour period, and the water gushed through sections of the North Road between Mammoth and Gardiner, and three sections of the Northeast Road between Lamar Valley and Cooke City.

A large portion of the trail to the Boiling River was completely washed away and the river channel itself was drastically altered, rendering it inaccessible as of this writing. I refused to believe it when the news came out but have since verified with my own eyeballs that it’s true. Even if those factors weren’t true, the Old Gardiner Road, constructed in 1879, was toast.

Like a lot of natural events, people tend to think of such things as “disasters.” I’m guilty of this. Of course I selfishly wish this hadn’t happened. (Where am I supposed to go for my birthday now?) But Mother Nature is just being herself. We’re sitting on a super volcano, after all – Yellowstone is constantly cooking and doing other things that might not be convenient for humans. All the money and human willpower in the world can’t control nature. What a privilege, then, to be here, now, and experience the wonders of Yellowstone – enjoy them while you can!