By Fischer Genau

DISCLAIMER: This story tracks the movements of “Bruno,” a male grizzly bear from the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem. Bruno is a creation of the author and does not reflect data gathered on any specific grizzly, although it aims to present a plausible male grizzly bear in Montana.

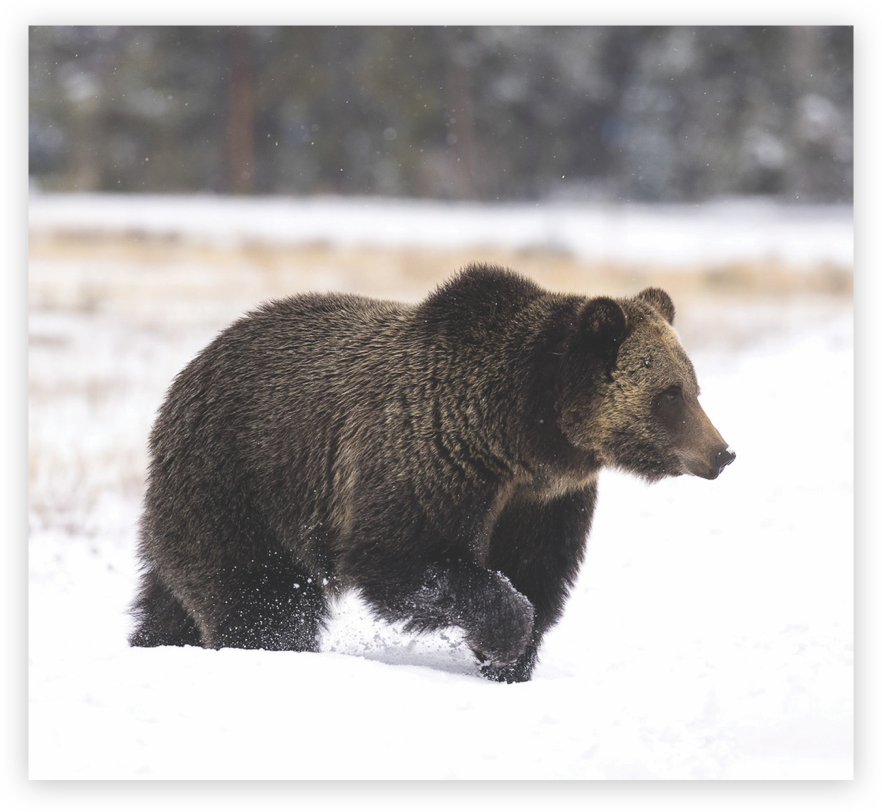

Bruno was born in January, blind and about the size of a Coke can. The first two months of his life were spent in complete darkness, nursing with his sister in his mother’s den, and by the time they dug their way out in April, he had grown tenfold in size. During their first year, Bruno and his sister shadowed their mother, learning how to dig insects out of fallen logs and forage for the tender spring shoots that grow in their valley. But by the time they returned to the den for the winter, only Bruno and his mother remained. Life is perilous for cubs, and his sister was unlucky.

When he left the den a second time, Bruno was 100 times bigger than he was at birth, and now, another year later, Bruno has reached the size of a small adult black bear. He and his mother live in the Porcupine Basin, near the southern end of Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, an area of 1.5 million acres that contains hundreds of grizzlies. But already his time there is coming to an end. Bruno will return to the den this winter with his mother, but when they exit in the spring, she will turn hostile towards him. After two or three years, females are ready to mate again, and they drive off the offspring they just raised. Bruno will be left to fend for himself, turning his back on the valley he grew up in and setting off on his own.

When he left the den a second time, Bruno was 100 times bigger than he was at birth, and now, another year later, Bruno has reached the size of a small adult black bear. He and his mother live in the Porcupine Basin, near the southern end of Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, an area of 1.5 million acres that contains hundreds of grizzlies. But already his time there is coming to an end. Bruno will return to the den this winter with his mother, but when they exit in the spring, she will turn hostile towards him. After two or three years, females are ready to mate again, and they drive off the offspring they just raised. Bruno will be left to fend for himself, turning his back on the valley he grew up in and setting off on his own.

Bruno is one of about 2,000 grizzly bears living in the lower 48. Grizzlies in the contiguous United States once numbered over 50,000, roaming from the West Coast to the Great Plains and all the way down into the heart of Mexico. But after the arrival of European settlers, the species was decimated and confined to two geographic areas: the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), which includes Yellowstone National Park and its surrounding areas, and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (NCDE), a region of 16,000 square miles that runs from Glacier National Park all the way down to Lincoln, Montana—40 miles from the

Porcupine Basin.

At their nadir, there were only about 700 grizzlies in the U.S., excluding Alaska. But aided by the efforts of conservationists, the species has made a comeback. Scientists now estimate that about 1,000 grizzly bears live in the GYE, and another 1,000 in the NCDE (there are also small grizzly populations in the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem and the Selkirk Mountains in northern Idaho, but those are estimated at less than 100). Yet grizzlies only occupy a small fraction of their former range, and as of August 2025, grizzly populations in the NCDE and the GYE don’t overlap. Conservationists’ next big push is to unite them.

Porcupine Basin.

At their nadir, there were only about 700 grizzlies in the U.S., excluding Alaska. But aided by the efforts of conservationists, the species has made a comeback. Scientists now estimate that about 1,000 grizzly bears live in the GYE, and another 1,000 in the NCDE (there are also small grizzly populations in the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem and the Selkirk Mountains in northern Idaho, but those are estimated at less than 100). Yet grizzlies only occupy a small fraction of their former range, and as of August 2025, grizzly populations in the NCDE and the GYE don’t overlap. Conservationists’ next big push is to unite them.

“Our ultimate goal is to have one regionally connected grizzly bear population that's resilient enough to sustain itself against continued human encroachment and continued climate change,” says Ryan Lutey, the Executive Director for Vital Ground. “That doesn't mean there has to be a bear behind every rock out there, but the landscape has to be healthy enough to support a healthy population, and also humans have to be tolerant enough to permit that and promote that as well.”

Vital Ground is a land trust based in Missoula that conserves and connects habitat for grizzly bears and other wildlife. Through their One Landscape Initiative, they protect private lands in key connectivity areas through conservation easements, land purchases, and other methods to clear a path for grizzlies to retake their former range.

So far, grizzlies have expanded successfully from five of six recovery zones that were established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1975 (the sixth, the Northern Cascades, no longer holds a viable population and only sees an occasional bear roaming south from British Columbia). Their return is one of conservation’s biggest success stories. But to achieve a regionally connected, resilient population, grizzlies still have a long way to go.

Vital Ground is a land trust based in Missoula that conserves and connects habitat for grizzly bears and other wildlife. Through their One Landscape Initiative, they protect private lands in key connectivity areas through conservation easements, land purchases, and other methods to clear a path for grizzlies to retake their former range.

So far, grizzlies have expanded successfully from five of six recovery zones that were established by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1975 (the sixth, the Northern Cascades, no longer holds a viable population and only sees an occasional bear roaming south from British Columbia). Their return is one of conservation’s biggest success stories. But to achieve a regionally connected, resilient population, grizzlies still have a long way to go.

By fall of the next year, Bruno is three years old and 40 miles south of his birthplace, walking along Lyons Creek north of Helena. He’s still not strong enough to compete with adult males for a mate, but in the direction he’s going, he won’t have to worry about that for a while. Bruno is moving farther and farther away from other grizzlies, and only a few roaming bears, mostly lone males like himself, occupy the landscape between him and the GYE, still a hundred miles away. To traverse that distance is a long shot, and yet Bruno presses on.

The reasons for male grizzly dispersal are varied. Evolution has endowed males with a tendency to move away from the area they were born to reduce inbreeding, but most don’t travel more than about 30 miles. Bears that journey further sometimes do so to avoid competition with other bears for food and mates, but why some “outlier” bears (which Bruno would be classified as) travel hundreds of miles from their birthplace is not

always clear.

Right now, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service estimates that only 62 miles lie between the southernmost edge of the NCDE bears’ range and the northernmost tip of the GYE. A motivated male could easily bridge that gap. So far, there haven’t been any documented cases of a grizzly doing so, but it’s only a matter of time. Still, lone males crossing over wouldn’t result in true connectivity.

always clear.

Right now, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service estimates that only 62 miles lie between the southernmost edge of the NCDE bears’ range and the northernmost tip of the GYE. A motivated male could easily bridge that gap. So far, there haven’t been any documented cases of a grizzly doing so, but it’s only a matter of time. Still, lone males crossing over wouldn’t result in true connectivity.

For that to happen, female grizzlies would have to bridge the gap as well, and that will happen much more slowly. Females typically relocate only when bear populations become so dense that they must compete for food and range, and they don’t tend to cover the same distances that males do. Experts say this kind of connectivity could happen in the next 10-20 years, although it’s very hard to predict and will depend on many factors.

Reclaiming their historic range is not the only reason that conservationists want to achieve connectivity. It would also provide a genetic advantage. Right now, grizzly bears in the GYE are siloed off from the broader gene pool, and scientists are concerned that this could eventually lead to a loss of

genetic diversity.

“If you think about genetic diversity, it’s kind of like having a big variety of building blocks that a population can draw from,” says Cecily Costello, the head bear biologist for Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. “If there’s change in the environment in the future, and you have a lot of variety within your population, then at least some of those individuals will have the genetic traits to help adapt to that change.”

Costello says that while there is no immediate danger for the genetic health of Yellowstone’s grizzlies, bear biologists and conservationists are planning for the long term. Lutey from Vital Ground also says that grizzlies are an umbrella species, meaning that their health corresponds to the health of all sorts of other wildlife whose habitat overlaps with theirs. If grizzly bears roamed all the way from Lander, Wyoming to Alaska, it would be a sign of a

healthy landscape.

But connection won’t be easy.

Reclaiming their historic range is not the only reason that conservationists want to achieve connectivity. It would also provide a genetic advantage. Right now, grizzly bears in the GYE are siloed off from the broader gene pool, and scientists are concerned that this could eventually lead to a loss of

genetic diversity.

“If you think about genetic diversity, it’s kind of like having a big variety of building blocks that a population can draw from,” says Cecily Costello, the head bear biologist for Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. “If there’s change in the environment in the future, and you have a lot of variety within your population, then at least some of those individuals will have the genetic traits to help adapt to that change.”

Costello says that while there is no immediate danger for the genetic health of Yellowstone’s grizzlies, bear biologists and conservationists are planning for the long term. Lutey from Vital Ground also says that grizzlies are an umbrella species, meaning that their health corresponds to the health of all sorts of other wildlife whose habitat overlaps with theirs. If grizzly bears roamed all the way from Lander, Wyoming to Alaska, it would be a sign of a

healthy landscape.

But connection won’t be easy.

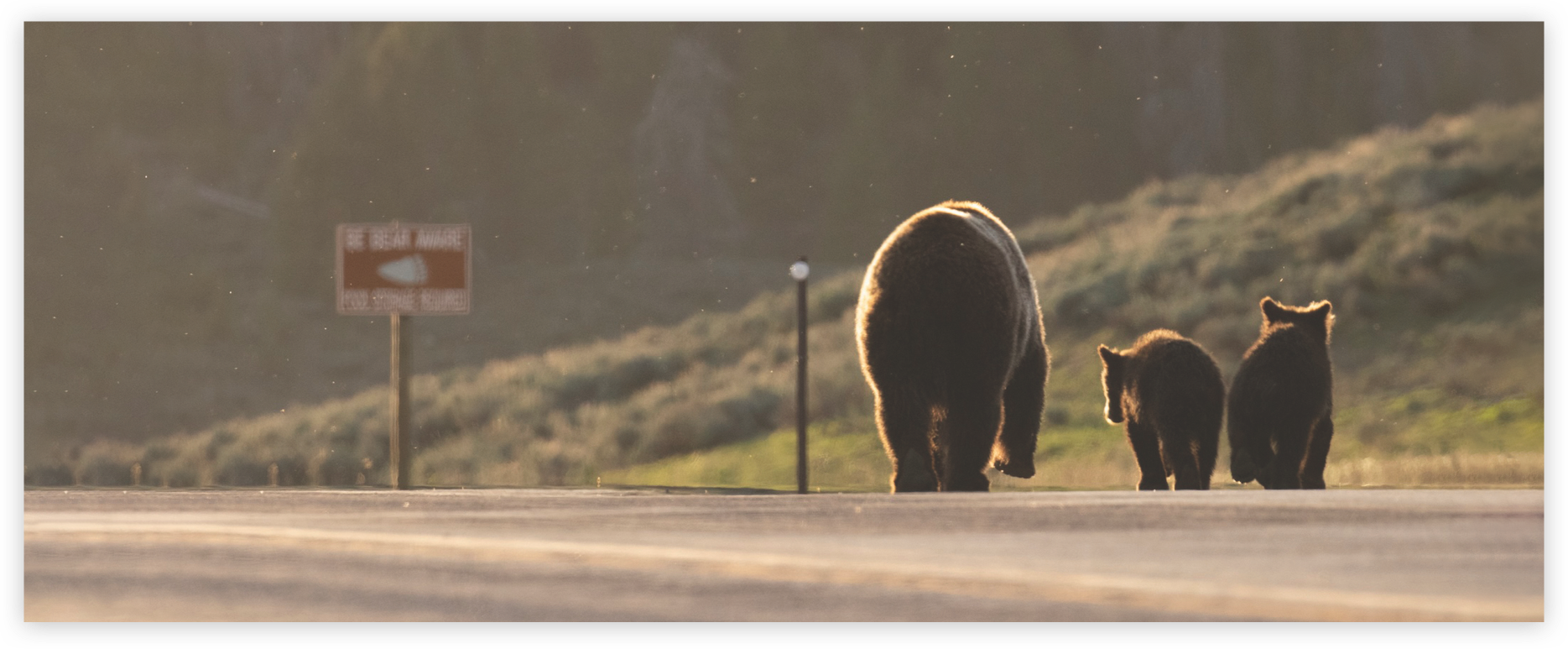

A roar, a blinding flash, and a shining object whips away into the night. Bruno stands concealed in a thicket of chokecherries beside I-15, the second road he’s encountered so far. The passing cars are disorienting, but there are less now than when he first tried to cross the four lanes. That time he only made it a few steps onto the concrete before a projectile whizzed towards him and he scurried back into the bushes. But he’s ready to try again. Bruno exits the thicket slowly, swinging his head left and right and sniffing the night air. As he reaches the median, Bruno feels a sudden rush of wind. Another car whooshes by, but this time Bruno is safely to the other side, and he presses on into the darkness.

In order to bridge the gap between the NCDE and the GYE, a grizzly must run a gauntlet of human-created obstacles.

“When you sit down and seriously look at a map, you quickly find out that the opportunities left to protect wildlife linkage are very few and far between, because people have so deftly inhabited and broken up the landscape,” Lutey said.

In the hundreds of years since grizzly bears roamed the continent, humans have been busy, and even for an adventurous male, navigating the web of farmland, ranches, towns, and roads between the two ecosystems is difficult. From 2020 to 2021, a bear dubbed Lingenpolter by the Montana FWP biologists tracking him tried to cross Highway 90 near Drummond, Montana over 50 times before finally making it over. Even a single highway can be very disruptive to a grizzly.

Vital Ground is working to make passage easier for wandering bears like Lingenpolter. In the 2010s, the land trust organized roundtable meetings with biologists, grizzly bear managers, and land managers from several federal agencies to decide which areas they should concentrate on to connect grizzly habitat. The resulting report, published in 2018, identified 33 priority areas and 188,000 acres of habitat, scattered across the NCDE, GYE, and Cabinet-Yaak and Selkirk ecosystems, that would help grizzlies move across the landscape.

One priority area was the Ninemile Crossing, a 52-acre area along the Clark Fork River that connects the NCDE to the Bitterroot Ecosystem. Vital Ground purchased the Ninemile in 2018 with the Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative, another habitat protection group, ensuring that a wildlife pathway used by grizzlies would remain undeveloped. Other habitat protection projects include Donovan Creek east of Missoula, Fowler Creek near the Yaak Valley, and Bismark Meadows in the Selkirk Mountains. All told, since Vital Ground’s founding in 1990, the land trust has helped protect over 1 million acres. Each purchase or conservation easement makes the landscape just a little more porous to allow more and more grizzlies to pass through.

But land protection is only half the battle. The second half of Vital Ground’s 2018 report focuses on conflict prevention, because as bears venture out from their recovery zones, some of them will inevitably cross paths with us.

“When you sit down and seriously look at a map, you quickly find out that the opportunities left to protect wildlife linkage are very few and far between, because people have so deftly inhabited and broken up the landscape,” Lutey said.

In the hundreds of years since grizzly bears roamed the continent, humans have been busy, and even for an adventurous male, navigating the web of farmland, ranches, towns, and roads between the two ecosystems is difficult. From 2020 to 2021, a bear dubbed Lingenpolter by the Montana FWP biologists tracking him tried to cross Highway 90 near Drummond, Montana over 50 times before finally making it over. Even a single highway can be very disruptive to a grizzly.

Vital Ground is working to make passage easier for wandering bears like Lingenpolter. In the 2010s, the land trust organized roundtable meetings with biologists, grizzly bear managers, and land managers from several federal agencies to decide which areas they should concentrate on to connect grizzly habitat. The resulting report, published in 2018, identified 33 priority areas and 188,000 acres of habitat, scattered across the NCDE, GYE, and Cabinet-Yaak and Selkirk ecosystems, that would help grizzlies move across the landscape.

One priority area was the Ninemile Crossing, a 52-acre area along the Clark Fork River that connects the NCDE to the Bitterroot Ecosystem. Vital Ground purchased the Ninemile in 2018 with the Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative, another habitat protection group, ensuring that a wildlife pathway used by grizzlies would remain undeveloped. Other habitat protection projects include Donovan Creek east of Missoula, Fowler Creek near the Yaak Valley, and Bismark Meadows in the Selkirk Mountains. All told, since Vital Ground’s founding in 1990, the land trust has helped protect over 1 million acres. Each purchase or conservation easement makes the landscape just a little more porous to allow more and more grizzlies to pass through.

But land protection is only half the battle. The second half of Vital Ground’s 2018 report focuses on conflict prevention, because as bears venture out from their recovery zones, some of them will inevitably cross paths with us.

At the age of four, Bruno has traveled over 150 miles from where he was raised. Most grizzlies roam thousands of miles in a lifetime, but those movements are usually limited to a specific region—Bruno is an explorer. His last move brought him from Elkhorn to the mountains east of Butte and down into the valley below, where he’s about to have his first real brush with civilization.

Bruno’s nose is stronger than a bloodhound’s, and it can detect an animal carcass from several miles away. It can also get him into trouble. Right now, it’s leading him to a garbage can tucked behind the garage of a home up in the hills, and his olfactory system is awash in the aroma of rotting fruit and chicken bones. It’s dusk, and as Bruno walks, he can see lights twinkling in the city below. When he nears the garage, he stops, ears pricked for any sign of danger, but he can’t resist the now-overpowering smells that promise him an easy meal. Within five minutes, the contents of the garbage can are strewn all over the concrete, and Bruno is munching on vegetable peelings when a door creaks open and the air explodes around him. He bounds away, back the way he came, reaching 30 miles per hour in his mad dash for survival. It’s a mile before he stops running.

Bruno is lucky. After that warning shot, he won’t be prying into more garbage cans any time soon. He’ll stick instead to mountains and densely forested areas, only traveling through human settlements when he must, and even then, going mostly by night. If he is to survive in this new landscape, he must adapt.

Bruno’s nose is stronger than a bloodhound’s, and it can detect an animal carcass from several miles away. It can also get him into trouble. Right now, it’s leading him to a garbage can tucked behind the garage of a home up in the hills, and his olfactory system is awash in the aroma of rotting fruit and chicken bones. It’s dusk, and as Bruno walks, he can see lights twinkling in the city below. When he nears the garage, he stops, ears pricked for any sign of danger, but he can’t resist the now-overpowering smells that promise him an easy meal. Within five minutes, the contents of the garbage can are strewn all over the concrete, and Bruno is munching on vegetable peelings when a door creaks open and the air explodes around him. He bounds away, back the way he came, reaching 30 miles per hour in his mad dash for survival. It’s a mile before he stops running.

Bruno is lucky. After that warning shot, he won’t be prying into more garbage cans any time soon. He’ll stick instead to mountains and densely forested areas, only traveling through human settlements when he must, and even then, going mostly by night. If he is to survive in this new landscape, he must adapt.

If grizzlies continue their recovery, human-grizzly conflict is bound to increase. Most of the bears in the lower 48 live in remote areas, like public lands or national forests, that are far from human settlements. This makes it easier for the two species to avoid each other, but as grizzlies spread further and further from their recovery zones, they will come into closer and closer contact with people.

“They’re expanding into a whole different sort of environment,” says Costello.

Costello runs a trend monitoring program through FWP, and she has documented “outlier” bears in places like the Big Hole Valley, the Elkhorn Mountains, and as far away as the Snowy Mountains near Lewistown. Many of these outlier bears are cropping up near rural communities, ranches, and farms, and they pose a challenge to the people living there who aren’t accustomed to living with grizzlies. When they arrive, groups like Vital Ground want to make sure they aren't rejected.

“They’re expanding into a whole different sort of environment,” says Costello.

Costello runs a trend monitoring program through FWP, and she has documented “outlier” bears in places like the Big Hole Valley, the Elkhorn Mountains, and as far away as the Snowy Mountains near Lewistown. Many of these outlier bears are cropping up near rural communities, ranches, and farms, and they pose a challenge to the people living there who aren’t accustomed to living with grizzlies. When they arrive, groups like Vital Ground want to make sure they aren't rejected.

“We can protect all the habitat we want, but if the bears aren't accepted out there on the landscape, it might be for naught,” says Mitch Doherty, the conservation director for Vital Ground.

Vital Ground has a grant program that awards money each year to communities that are deemed priority zones for reducing human-bear conflict. These efforts focus on promoting bear-safe protocol, like locking up garbage, eliminating the dumping of animal carcasses, and otherwise removing attractants that could draw grizzlies into an area. This year, they also invested in a drone with infrared sensing for Montana FWP grizzly bear technicians in Conrad, Montana—the drone can detect grizzlies from the air and even haze them away from livestock or other human activities. Lutey says that Vital Ground’s goal is to get money into the hands of community members, so they can launch their own grassroots efforts to manage living with bears.

Vital Ground has a grant program that awards money each year to communities that are deemed priority zones for reducing human-bear conflict. These efforts focus on promoting bear-safe protocol, like locking up garbage, eliminating the dumping of animal carcasses, and otherwise removing attractants that could draw grizzlies into an area. This year, they also invested in a drone with infrared sensing for Montana FWP grizzly bear technicians in Conrad, Montana—the drone can detect grizzlies from the air and even haze them away from livestock or other human activities. Lutey says that Vital Ground’s goal is to get money into the hands of community members, so they can launch their own grassroots efforts to manage living with bears.

“We’re not there to tell them what to do,” says Lutey. “We’re there to offer incentive-based ways to live with grizzlies on their landscape, and we fully recognize that if there’s a bear that is too obstinate about it, those bears need to be managed.”

Erik Kalsta, whose family started ranching in the Big Hole Valley in 1896, has been dealing with bears on his property for decades. Their first grizzly appeared all the way back in 1982, when bears weren’t thought to have wandered that far from their recovery zones. In 2003, a young female arrived and scratched up some of their heifers before giving up to prey on elk, and in 2007, another young grizzly, this time a male, appeared on their ranch, but his worst offense was stealing the float ball from their remote water trough. Kalsta and the three other owners that share the property have adjusted some of their practices in response to the presence of grizzlies on the landscape. When animals die, they move carcasses to a remote area, and when one of them approaches a dense timber patch or heavily willowed stream bottom where bears like to hang out, they do so with caution.

“We know that there will be problems, we absolutely know that, but at this point we are doing our best to manage around that,” Kalsta said. “We don’t want there to be problems, for our sake and the bear’s sake, but mostly for ours.”

Kalsta also works with Western Land Alliance as the program director for their Working Wild Challenge, which aims to address the challenges of ranching with wildlife. The program emphasizes collaboration, conflict prevention tools, compensating ranchers for killed cattle and other costs from grizzlies living on the landscape, and the occasional need for lethal control.

Kalsta said that while ranching is a lifestyle, it’s also a business: “they have to stay solvent for us to remain on the landscape.” Kalsta wants to ensure that ranches in grizzly-populated areas remain financially viable so they’re not sold off and turned into subdivisions, which would effectively eliminate

bear habitat.

As Kalsta says, there will be problems. But people like Costello and Lutey hope that through education and awareness, people will come to see the tradeoffs of living with grizzlies as worthwhile. “Our founder always says, ‘Where the grizzly can walk, the earth is healthy and whole,’” says Lutey.

“I think people have respect for carnivores, but they always want them to live somewhere else,” says Costello. “I think it would be nice if we started thinking of Montana and these Northern Rockies states as grizzly country, where we can live with them and not apart from them.”

Erik Kalsta, whose family started ranching in the Big Hole Valley in 1896, has been dealing with bears on his property for decades. Their first grizzly appeared all the way back in 1982, when bears weren’t thought to have wandered that far from their recovery zones. In 2003, a young female arrived and scratched up some of their heifers before giving up to prey on elk, and in 2007, another young grizzly, this time a male, appeared on their ranch, but his worst offense was stealing the float ball from their remote water trough. Kalsta and the three other owners that share the property have adjusted some of their practices in response to the presence of grizzlies on the landscape. When animals die, they move carcasses to a remote area, and when one of them approaches a dense timber patch or heavily willowed stream bottom where bears like to hang out, they do so with caution.

“We know that there will be problems, we absolutely know that, but at this point we are doing our best to manage around that,” Kalsta said. “We don’t want there to be problems, for our sake and the bear’s sake, but mostly for ours.”

Kalsta also works with Western Land Alliance as the program director for their Working Wild Challenge, which aims to address the challenges of ranching with wildlife. The program emphasizes collaboration, conflict prevention tools, compensating ranchers for killed cattle and other costs from grizzlies living on the landscape, and the occasional need for lethal control.

Kalsta said that while ranching is a lifestyle, it’s also a business: “they have to stay solvent for us to remain on the landscape.” Kalsta wants to ensure that ranches in grizzly-populated areas remain financially viable so they’re not sold off and turned into subdivisions, which would effectively eliminate

bear habitat.

As Kalsta says, there will be problems. But people like Costello and Lutey hope that through education and awareness, people will come to see the tradeoffs of living with grizzlies as worthwhile. “Our founder always says, ‘Where the grizzly can walk, the earth is healthy and whole,’” says Lutey.

“I think people have respect for carnivores, but they always want them to live somewhere else,” says Costello. “I think it would be nice if we started thinking of Montana and these Northern Rockies states as grizzly country, where we can live with them and not apart from them.”

After six years of wandering, Bruno enters the McAtee Basin in the Madison Range, over 200 miles from where he was born. He’s not alone. With him is a younger female, a member of the GYE population, and the two are about to mate. Their offspring will carry a combination of their mother and father’s genes, one from the north and one from the south, and those cubs, with a little luck, will go off to have kids of their own.

The road for Bruno to get here was long and difficult, but others will follow. At first, they’ll be roving males, heeding their evolutionary charge to expand and explore. Then the females will come, slowly pushing out from densely populated areas to find food and raise their offspring. In time, grizzly populations from the northernmost tip of Alaska down to central Wyoming will connect as, one by one, the bears return to their old stomping grounds.

The road for Bruno to get here was long and difficult, but others will follow. At first, they’ll be roving males, heeding their evolutionary charge to expand and explore. Then the females will come, slowly pushing out from densely populated areas to find food and raise their offspring. In time, grizzly populations from the northernmost tip of Alaska down to central Wyoming will connect as, one by one, the bears return to their old stomping grounds.

For now, that future is a fantasy. Grizzlies’ expansion will put them closer and closer to the settlements that humans built in the bears’ long absence, and it will be an uneasy homecoming. Reaching connectivity will depend on the work of people like Lutey, Costello, and Kalsta, as well as the collective attitude of thousands who may soon have to come to terms with the presence of grizzly bears on the landscape.

But grizzlies will keep pressing out from their sanctuaries if we let them. It may not be long before the grizzlies come home.

But grizzlies will keep pressing out from their sanctuaries if we let them. It may not be long before the grizzlies come home.