For much of the nineteenth century, Yellowstone National Park existed in the American imagination as both myth and rumor: a landscape of fire and ice, geysers that roared like cannons, and canyons carved by boiling rivers. To most however, it was inaccessible. Early travel meant enduring weeks on horseback or rattling stagecoaches along rough trails.

That remoteness was a defining feature of Yellowstone’s earliest decades as a national park. When Congress set aside the land in 1872, creating the world’s first national park, no railroads ran through the region. Access meant endurance. The first official visitors were military details, scientists, and artists who made these long treks.

Yet the idea of Yellowstone was already spreading. Its very inaccessibility enhanced its mystique: a wilderness set apart, protected but not easily reached.

by Taylor Owens

The Legacy of Train Travel to and from Yellowstone

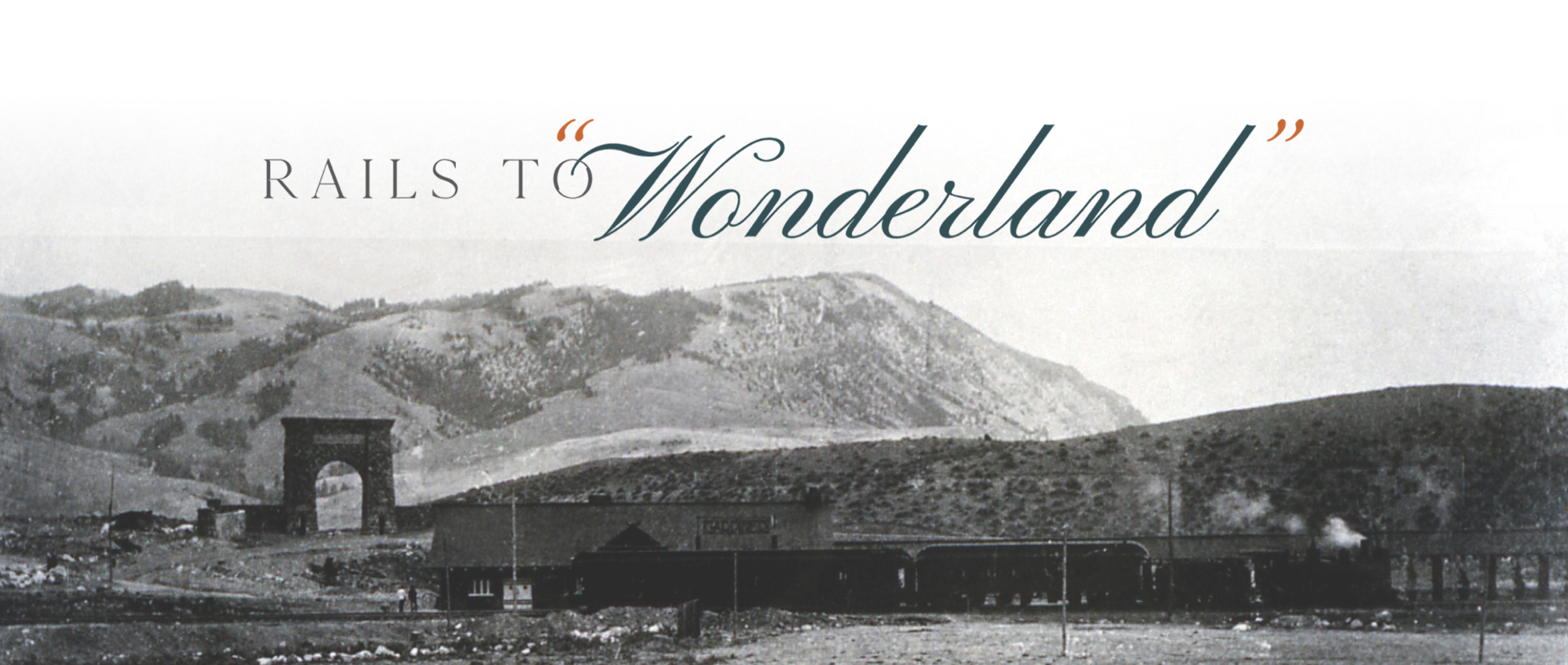

Train at Gardiner; Photographer unknown; No date. PHOTO COURTESY OF NPS

In the decades between Yellowstone’s designation as a park and the first arrival of trains at its borders, the only way in was overland. Stagecoaches rumbled from the closest rail stop, carrying tourists from distant areas in the United States who had traveled as far as they could across the country via rail. The trips were costly, dusty, and unpredictable, but for the growing number of travelers drawn by paintings, photographs, and sensational reports of geysers, they were worth it.

Still, this early stagecoach era underscored the limits of Yellowstone tourism. Visitor numbers remained relatively small, access was confined to those with means, and the experience itself was grueling.

By the late 1880s, as rails stretched across the West and rail companies eyed the prestige of being the “gateway to Wonderland,” the whistle of locomotives began to echo closer to Yellowstone’s borders.

Still, this early stagecoach era underscored the limits of Yellowstone tourism. Visitor numbers remained relatively small, access was confined to those with means, and the experience itself was grueling.

By the late 1880s, as rails stretched across the West and rail companies eyed the prestige of being the “gateway to Wonderland,” the whistle of locomotives began to echo closer to Yellowstone’s borders.

“The railroads, particularly the Northern Pacific, had significant impact even on the park being established,” Alicia Murphy, Yellowstone National Park’s historian, said. “The relationship between national parks and train travel is kind of difficult to overstate from the very beginning.”

If any town claimed the honor of being Yellowstone’s first rail-linked entrance, it was Livingston, Montana. By the early 1880s, the Northern Pacific Railroad had established Livingston as a division point, then built a spur line south up Paradise Valley to Cinnabar, just short of Gardiner. Not until 1903 did the tracks finally reach the park’s boundary and the stone archway at its northern gate.

This was more than tracklaying; it was place-making. The Northern Pacific positioned Livingston as the northern gateway to Yellowstone, marketing the town as the starting point of an unforgettable journey into America’s wonderland. The company printed elaborate brochures, stocked with engravings of geysers and canyons, and distributed them across the country.

In Gardiner, the park’s northern entrance took shape. “That was considered kind of Yellowstone’s front door,” said Murphy. The depot welcomed guests who would then transfer to stagecoaches waiting just outside the tracks. By 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt dedicated the famous Roosevelt Arch at Gardiner’s boundary, a grand stone that marked the park boundary and became an enduring symbol of Yellowstone’s accessibility in the age of rail travel.

For decades, the North Entrance became the iconic first stop for thousands of Yellowstone visitors.

In 1908, the Oregon Short Line, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific, completed a branch from Idaho Falls to a brand-new town: West Yellowstone.

If any town claimed the honor of being Yellowstone’s first rail-linked entrance, it was Livingston, Montana. By the early 1880s, the Northern Pacific Railroad had established Livingston as a division point, then built a spur line south up Paradise Valley to Cinnabar, just short of Gardiner. Not until 1903 did the tracks finally reach the park’s boundary and the stone archway at its northern gate.

This was more than tracklaying; it was place-making. The Northern Pacific positioned Livingston as the northern gateway to Yellowstone, marketing the town as the starting point of an unforgettable journey into America’s wonderland. The company printed elaborate brochures, stocked with engravings of geysers and canyons, and distributed them across the country.

In Gardiner, the park’s northern entrance took shape. “That was considered kind of Yellowstone’s front door,” said Murphy. The depot welcomed guests who would then transfer to stagecoaches waiting just outside the tracks. By 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt dedicated the famous Roosevelt Arch at Gardiner’s boundary, a grand stone that marked the park boundary and became an enduring symbol of Yellowstone’s accessibility in the age of rail travel.

For decades, the North Entrance became the iconic first stop for thousands of Yellowstone visitors.

In 1908, the Oregon Short Line, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific, completed a branch from Idaho Falls to a brand-new town: West Yellowstone.

“There was no town there before the railroad,” Thornton Waite, railroad historian and author of Yellowstone by Train: A History of Rail Travel to America’s First National Park, said. “I would guess the railroad had the greatest impact on the development of West Yellowstone because it was literally created by the line.”

At the edge of the park boundary, the Union Pacific constructed a depot and a collection of rustic-style buildings designed to accommodate tourists. The company’s promotional machine went into overdrive, advertising sleek new trains like the Yellowstone Special and promising direct, comfortable access to Wonderland.

The line was unique due to its seasonality. Unlike most mainline railroads, the West Yellowstone branch closed every winter. “Every winter they allowed the line to be snowed shut,” Waite explained. “That was very unusual — most railroads would do whatever it took to keep a line open. But here, the line existed only to serve summer visitors.”

At the edge of the park boundary, the Union Pacific constructed a depot and a collection of rustic-style buildings designed to accommodate tourists. The company’s promotional machine went into overdrive, advertising sleek new trains like the Yellowstone Special and promising direct, comfortable access to Wonderland.

The line was unique due to its seasonality. Unlike most mainline railroads, the West Yellowstone branch closed every winter. “Every winter they allowed the line to be snowed shut,” Waite explained. “That was very unusual — most railroads would do whatever it took to keep a line open. But here, the line existed only to serve summer visitors.”

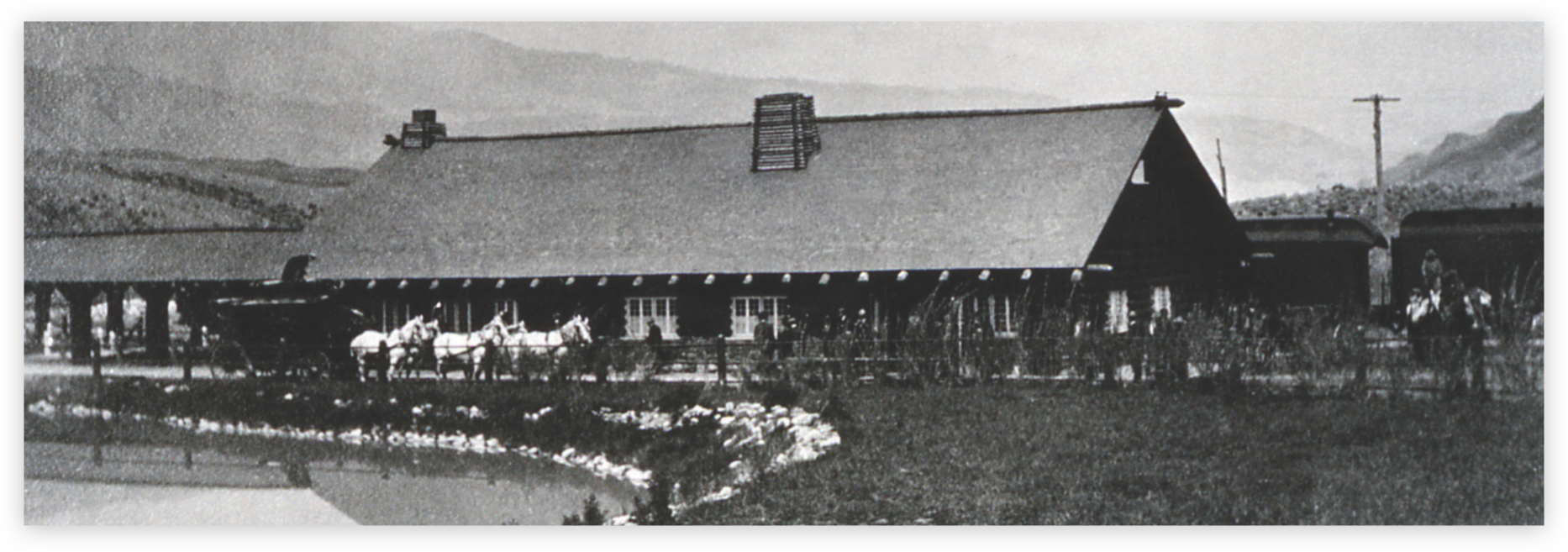

Oregon Short Line depot in West Yellowstone, Montana; JP Clum Lantern slide; Around 1908. PHOTO COURTESY OF NPS

Each fall, as snow closed the line, West slipped into hibernation. Each spring, when crews cleared the tracks and trains returned, the town reawakened for what Waite referred to as “the spring campaign.”

“It was a two-to-four-day process to clear the line for 50 miles from Ashton up to West Yellowstone,” Waite said. “The arrival of the train was a big event. Even afterwards, they had a big party because it meant winter was over, and summer was coming, the tourists were coming, and, things were looking up. Some of the pictures show the snow [being cleared] was deeper than the train was high.”

The contrast between north and west reveals two models of railroad impact. Livingston and Gardiner adapted existing towns into gateways, layering rail access atop the already-established rail or mining communities. West Yellowstone, by contrast, was a manufactured node of tourism, designed from the ground up by a railroad with a single purpose.

Both exemplified the way railroads reshaped access to Yellowstone. They shortened journeys from weeks to days, opened the park to middle-class travelers, and embedded Yellowstone in the national consciousness as a destination not just for the hardy or the wealthy, but for anyone who could buy a ticket.

On the park’s eastern flank, the Burlington Railroad reached the frontier town of Cody, Wyoming, in 1901. Cody itself was co-founded by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who quickly recognized the economic potential of rail access to the park. The Burlington marketed Cody as the “Scenic Gateway” to Yellowstone, offering travelers a route that passed through the Absaroka Mountains and the Shoshone River.

Though the eastern route never rivaled the north or west in sheer numbers, it reflected the competitive spirit of the era. Every railroad wanted to claim Yellowstone as part of its domain, and every town along the rails sought the prestige, and economic boost, of being a gateway.

“It was a two-to-four-day process to clear the line for 50 miles from Ashton up to West Yellowstone,” Waite said. “The arrival of the train was a big event. Even afterwards, they had a big party because it meant winter was over, and summer was coming, the tourists were coming, and, things were looking up. Some of the pictures show the snow [being cleared] was deeper than the train was high.”

The contrast between north and west reveals two models of railroad impact. Livingston and Gardiner adapted existing towns into gateways, layering rail access atop the already-established rail or mining communities. West Yellowstone, by contrast, was a manufactured node of tourism, designed from the ground up by a railroad with a single purpose.

Both exemplified the way railroads reshaped access to Yellowstone. They shortened journeys from weeks to days, opened the park to middle-class travelers, and embedded Yellowstone in the national consciousness as a destination not just for the hardy or the wealthy, but for anyone who could buy a ticket.

On the park’s eastern flank, the Burlington Railroad reached the frontier town of Cody, Wyoming, in 1901. Cody itself was co-founded by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who quickly recognized the economic potential of rail access to the park. The Burlington marketed Cody as the “Scenic Gateway” to Yellowstone, offering travelers a route that passed through the Absaroka Mountains and the Shoshone River.

Though the eastern route never rivaled the north or west in sheer numbers, it reflected the competitive spirit of the era. Every railroad wanted to claim Yellowstone as part of its domain, and every town along the rails sought the prestige, and economic boost, of being a gateway.

Gardiner train depot, pond & stagecoaches; Photographer unknown; Around 1908. PHOTO COURTESY OF NPS

A visitor’s journey typically began in a distant city, Chicago, Minneapolis, or Omaha, traveling westward in relative comfort aboard sleeping and dining cars. At the park boundary, passengers disembarked into stagecoaches. Rudyard Kipling captured the experience: “Today I am in Yellowstone, and I wish I were dead,” a reflection of the jarring shift from rail to wagon.

Through subsidiaries like the Yellowstone Park Company, the Northern Pacific invested in hotels and concessions within the park. The Old Faithful Inn, completed in 1904, became both a symbol of rustic grandeur and a marketing tool, featured prominently in rail brochures.

Railroads were not merely transporters; they were curators. “Basically, they made it so people could get to the park, and you’d have a place to stay in the park,” Murphy said. They made sure you had a meal to eat, and an itinerary to follow. It was a packaged experience.

That packaging extended to how long visitors stayed. A standard tour often lasted five days: a circuit by stagecoach through the geyser basins, canyon, and lake, with overnights in company-run hotels.

“It was a standard travel experience,” Waite said. “I know that a lot of the people that traveled to Yellowstone via railroad were a lot of people from the East Coast and it was obviously a pretty expensive endeavor.” Despite the railroads’ efforts to broaden access, Yellowstone remained a destination for the relatively privileged. A full rail-and-stagecoach package could cost upward of $100 in the early 1900s — the equivalent of several thousand dollars today.

Within the trains themselves, the class divisions of American travel played out. First-class passengers enjoyed sleeper cars and fine dining; second-class passengers might ride in plainer coaches with fewer amenities. Once in the park however, those distinctions blurred somewhat — everyone endured the same jostling stagecoaches and accommodations.

In that sense, rail travel to Yellowstone was both democratizing and stratifying: more people could reach the park than ever before, but access was still defined by income.

Through subsidiaries like the Yellowstone Park Company, the Northern Pacific invested in hotels and concessions within the park. The Old Faithful Inn, completed in 1904, became both a symbol of rustic grandeur and a marketing tool, featured prominently in rail brochures.

Railroads were not merely transporters; they were curators. “Basically, they made it so people could get to the park, and you’d have a place to stay in the park,” Murphy said. They made sure you had a meal to eat, and an itinerary to follow. It was a packaged experience.

That packaging extended to how long visitors stayed. A standard tour often lasted five days: a circuit by stagecoach through the geyser basins, canyon, and lake, with overnights in company-run hotels.

“It was a standard travel experience,” Waite said. “I know that a lot of the people that traveled to Yellowstone via railroad were a lot of people from the East Coast and it was obviously a pretty expensive endeavor.” Despite the railroads’ efforts to broaden access, Yellowstone remained a destination for the relatively privileged. A full rail-and-stagecoach package could cost upward of $100 in the early 1900s — the equivalent of several thousand dollars today.

Within the trains themselves, the class divisions of American travel played out. First-class passengers enjoyed sleeper cars and fine dining; second-class passengers might ride in plainer coaches with fewer amenities. Once in the park however, those distinctions blurred somewhat — everyone endured the same jostling stagecoaches and accommodations.

In that sense, rail travel to Yellowstone was both democratizing and stratifying: more people could reach the park than ever before, but access was still defined by income.

Gardiner train depot; Photographer unknown; Around 1904. PHOTO COURTESY OF NPS

The visitor experience extended beyond logistics into ideology. Railroads promoted Yellowstone not just as a destination but as a symbol of American pride.

Railroads became some of the biggest champions of the national park idea. They had an economic incentive, but they also helped build the narrative that these were places all Americans should see. “Jay Cook, the American financier behind the Northern Pacific, was in the midst of extending the Northern Pacific from the East Coast to the West Coast, and he saw places like Yellowstone as a significant justification for these railroad expansions, and he lobbied very fiercely for the park to be set aside,” Murphy said.

Union Pacific’s “See America First” campaign captured this ethos, urging travelers to skip Europe in favor of domestic wonders. Posters depicted geysers as national monuments, and brochures promised an experience equal to the Alps or the Black Forest.

Railroads became some of the biggest champions of the national park idea. They had an economic incentive, but they also helped build the narrative that these were places all Americans should see. “Jay Cook, the American financier behind the Northern Pacific, was in the midst of extending the Northern Pacific from the East Coast to the West Coast, and he saw places like Yellowstone as a significant justification for these railroad expansions, and he lobbied very fiercely for the park to be set aside,” Murphy said.

Union Pacific’s “See America First” campaign captured this ethos, urging travelers to skip Europe in favor of domestic wonders. Posters depicted geysers as national monuments, and brochures promised an experience equal to the Alps or the Black Forest.

By riding the rails to Yellowstone, visitors weren’t just taking a vacation; they were participating in a story of national identity.

“In some ways, it’s interesting that [the railroads] were influential in creating this island of wilderness in Yellowstone—partially protected from development—because of the industrialization of the railroad,” Murphy said. “It’s an intriguing dichotomy.”

For all their influence, the railroads’ hold on Yellowstone tourism proved temporary. The very forces of modernity that had made the park accessible by train soon reshaped travel again, this time in the form of the automobile.

In 1915, private automobiles were officially allowed into Yellowstone. At first, the transition was halting. Roads were narrow, dusty, and not always suitable for the sputtering machines. Early visitors were required to obtain special permits, and convoys of cars were escorted to prevent accidents with stagecoaches still rumbling along the same routes.

Yet the freedom and affordability of the automobile quickly proved irresistible. Families who might never have afforded a full rail-and-stagecoach package could now pile into a Ford and drive themselves into the park. By the 1920s, automobile tourism surged, and stagecoach lines began

to vanish.

“Better roads was the real reason passenger travel declined and ended because everyone wanted to go in their private automobiles,” Waite said. “You’d have the freedom of your car when you arrived at the park instead of having to be in a tour group.”

The shift was starkest in the gateway towns. West Yellowstone, once animated by the seasonal rhythm of train arrivals, saw its great depot fall quiet. Livingston, Gardiner, Cody, and others all witnessed a decline in passenger service as demand evaporated. By the mid-twentieth century, most of the spur lines into Yellowstone had been abandoned or converted to freight.

Today, some of the old depots survive as museums, visitor centers, or community landmarks — physical reminders of the era when locomotives delivered thousands to Yellowstone’s edge. Certain routes like the route from Livingston to Gardiner “is slowly being turned into a kind of walking, hiking, biking trail … further kind of tying into that train history,” Murphy said.

The rails vanished, the cars took over — but the dream they sold still holds: Yellowstone is a place every American should see.

“In some ways, it’s interesting that [the railroads] were influential in creating this island of wilderness in Yellowstone—partially protected from development—because of the industrialization of the railroad,” Murphy said. “It’s an intriguing dichotomy.”

For all their influence, the railroads’ hold on Yellowstone tourism proved temporary. The very forces of modernity that had made the park accessible by train soon reshaped travel again, this time in the form of the automobile.

In 1915, private automobiles were officially allowed into Yellowstone. At first, the transition was halting. Roads were narrow, dusty, and not always suitable for the sputtering machines. Early visitors were required to obtain special permits, and convoys of cars were escorted to prevent accidents with stagecoaches still rumbling along the same routes.

Yet the freedom and affordability of the automobile quickly proved irresistible. Families who might never have afforded a full rail-and-stagecoach package could now pile into a Ford and drive themselves into the park. By the 1920s, automobile tourism surged, and stagecoach lines began

to vanish.

“Better roads was the real reason passenger travel declined and ended because everyone wanted to go in their private automobiles,” Waite said. “You’d have the freedom of your car when you arrived at the park instead of having to be in a tour group.”

The shift was starkest in the gateway towns. West Yellowstone, once animated by the seasonal rhythm of train arrivals, saw its great depot fall quiet. Livingston, Gardiner, Cody, and others all witnessed a decline in passenger service as demand evaporated. By the mid-twentieth century, most of the spur lines into Yellowstone had been abandoned or converted to freight.

Today, some of the old depots survive as museums, visitor centers, or community landmarks — physical reminders of the era when locomotives delivered thousands to Yellowstone’s edge. Certain routes like the route from Livingston to Gardiner “is slowly being turned into a kind of walking, hiking, biking trail … further kind of tying into that train history,” Murphy said.

The rails vanished, the cars took over — but the dream they sold still holds: Yellowstone is a place every American should see.